- Home

- Chris West

The Beijing Opera Murder Page 3

The Beijing Opera Murder Read online

Page 3

‘I want the name of the gang and the names of any individuals you knew. Then you can go. None of this will ever be on the record.’ He paused. ‘Of course, if you don’t tell me, we could keep you here for a very long time.’ He sat back and let silence get to work again.

‘Do you offer … informant protection?’ Meng said finally.

‘Officially, no. Unofficially we’ll keep a watch out for you. But right now nobody knows you’ve spoken to me, and I’m not telling anyone, so it shouldn’t be necessary.’

Meng did not look convinced. ‘How can I trust you?’

‘Have I ever broken my word in the past?’ said Bao. ‘I know, I’m not out on the streets any longer. They keep me behind a desk. But it hasn’t totally destroyed my sense of right and wrong. Or my need to keep my reputation good.’

Meng scowled.

‘I need to get things sorted out before Xiao Lu gets back,’ Bao went on. ‘He’s the son of a very senior Party official and does everything strictly by the rules.’ He let the silence fall again. ‘I’m feeling thirsty!’ he exclaimed after a while. ‘I’m so glad a nice mug of tea is on its way.’

Meng held out his hand and began tracing characters on it. Three of them. Yi Guan Dao.

Bao’s eyes widened.

The petty criminal laughed. ‘You think they’re ancient history, don’t you? The Party says the Triads have been – what’s the word they use? Suppressed. Don’t believe it.’

‘I shan’t,’ said Bao.

Lu was back with the tea.

*

Bao made his way down to the basement, where the Xing Zhen Ke library was based. He was hoping to find Chai there. Many years ago, when Bao first came to the capital, he and this man had worked on a case together and ‘clicked’. One evening, they had drunk too much and sworn brotherhood. A year or so later, Chai had been shot in the back by a gang of drug smugglers. Bao had worked extra hard to get the culprit brought to justice, and after the verdict, had asked to carry out the execution himself. Permission had been granted.

An assistant was on duty.

‘If you’d like to fill in this form, we can let you have three files to take away,’ she told him. ‘You are allowed to keep them for twenty-four hours, after which time you will have to get clearance from the fifth floor.’

There was a buzzing noise and Chai’s electric wheelchair rolled into view.

‘Bao Zheng!’ The occupant held out a hand, and Bao shook it with suitable warmth. ‘What can I do for you?’

‘I want all the information you’ve got on the Yi Guan Dao Triad.’

‘All of it?’

‘As much as you can spare. And I want it for as long as I need it.’

Chai nodded. ‘Miss Hu, give the inspector everything he asks for.’

The assistant opened her mouth to protest then went off.

‘So what brings about your interest in the Triads?’ Chai continued. ‘I thought you were investigating art thefts. Are the Yi Guan Dao involved in those?’

‘No. It’s a murder. Committed under my nose. Well, behind my back. Of a small-time hood who we think joined up.’

‘Chopped to bits with meat cleavers, was he?’

‘No, stabbed. But there’s a Triad link, so I need to follow it up.’

‘Ah. A bit like that business with the forged banknotes…’ The two old colleagues began reminiscing until Miss Hu appeared with two armfuls of files.

‘Those look heavy,’ said Bao. ‘Allow me.’

She glared at him. ‘I was runner-up in the all-China Police Athletics Association decathlon. I used to lift this weight fifty times a day. Where is your office?’

‘Third floor.’

‘Follow me, please.’

Up in the office, Miss Hu put the files on his desk, acknowledged the inspector’s thanks with the slightest of nods and walked out. Bao grinned, embarrassed by his own mixed reactions of annoyance and admiration. Then he selected a file at random and began to read.

Investigations into the activities of the Yi Guan Dao Triad, by Detective Inspector (First Class) Liu Qiang.

He glanced up at the clock. Half-past four. He’d skim through the stuff now and get home on time for once.

Next time he looked up, it had gone seven.

Chapter Three

Bao closed the file and stared blankly at its drab grey cover. His head spun with the information that lay within it. His colleague Liu’s findings supported Meng’s story. A Triad lodge had been set up in the capital, led by a figure known only as the Shan Master. The most senior figure for whom he had any possible identity was the lodge Red Stick (Enforcer), a man named Ren Hui, a businessman with good connections. The lodge appeared to be expanding. According to rumour, a swearing-in ceremony for ‘Blue Lanterns’ (new recruits) had been held about six months ago.

Liu had described what the ritual would be like.

To join a Triad meant to change your life, to die and to be born again ‒ hence the term ‘Blue Lantern’ (Bao still remembered the old custom of hanging such lanterns outside the homes of the dead). The initiation ceremony was designed to impress upon the youngsters the totality of their new commitment. Bao imagined the man he had seen in the mortuary going through it – Xun and probably four or five other young males, in grey, kneeling to receive burning incense sticks from the Shan Master, which they would then dash to the floor to simulate their fate if they broke the Triad code. Next, they would swear the thirty-six Oaths of Loyalty. Each would prick their middle finger and let the blood ooze into a cup, from which they all drank (still, Bao wondered, now this Western disease called AIDS was beginning to infect China?) The Incense Master, the lodge’s expert on ritual, would teach them the society’s codewords and recognition signals, then the Shan Master would invite them to step across a symbolic river of burning paper – a one-way journey, according to Oath Thirteen. Finally, they would take meat cleavers to an effigy of Ma Ningyi, the renegade monk who had betrayed the first Triad group, a reminder of the price of disloyalty.

Bao locked up his office and made his way down the stone steps of HQ into the main hall. The retired Special Forces sergeant on the front door wished him good night. Bao walked out into the smart concrete courtyard, then round to the rack at the rear of the building where his black Phoenix bicycle stood waiting for him. The motorbike he rode during work hours was a departmental one; only when he was Detective Inspector First Class would he have one that he could ride home. As he nosed the Phoenix out into the busy, jangling bike-lane of Qianmen East Street, he pondered what his next move should be. The author of that report, Liu – he must speak to him tomorrow morning.

A traffic light went red, and Bao pulled up. He wondered what Chen, Zhao and the rest of the team were doing now, back at Huashan.

Nothing remotely as interesting as this, he thought. He felt a big smile cross his face.

*

Bao put a call through first thing next morning.

‘Can I speak to Inspector Liu Qiang?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘He’s dead.’

‘Dead?’

‘Heart attack, three months ago.’

Bao’s eyes widened. ‘Are you busy?’

‘We’re always busy.’

‘I’m coming over now.’

*

Liu Qiang’s colleagues remembered him with little affection.

‘He was a loner,’ said his team leader. ‘An obsessive. I let him get on with his stuff as much as I could. He was very bitter about lack of support for his ideas.’ The man gave a shrug. ‘There was never enough money for the kind of investigation he wanted. He should have been born twenty years earlier. You know what it’s like now, everything has to be costed.’

Bao nodded.

‘He didn’t keep fit,’ the team leader went on. ‘And he smoked. You’ve read the latest Party directive on smoking, of course?’

‘Of course. Where did he die?’

‘H

ere. He often used to work over lunch break. He lived for his job. One day, I came back and found him slumped over his desk.’

‘Any clues as to ‒ ’

‘It was natural. We had a post-mortem, but there were no signs of any foul play. Most of us wondered why it hadn’t happened earlier.’

‘So it was common knowledge, his heart condition?’

‘Oh, yes. You’d only need to pass the poor old sod wheezing up the stairs. The day is waning and the road ending.’

Bao gave another nod. ‘Does he have any family?’

‘No.’

‘None?’

‘Not to our knowledge.’

Bao grimaced. Back in Nanping Village, life was still dominated by family and clan. Come to the capital…

‘I guess we do feel guilty we weren’t more friendly,’ the team leader said suddenly. ‘But he wasn’t the sociable type. We’d all go out for a meal sometimes. Eat a bit, drink a bit. He never came with us.’

‘Did he leave anything else apart from his Triad file?’

The team leader shook his head, but a sergeant began rummaging in a drawer.

‘His diary,’ he said, holding out a small green book.

Liu Qiang’s name was in the front, in correct, careful calligraphy. Then came a few appointments and a work schedule. January was to be dedicated to the Yi Guan Dao. A name was written at the top of one page: Luo Pang. From February onwards, there was nothing.

‘When did Liu die?’ Bao asked.

‘12 January.’

Bao returned to his own office, where he checked through Liu’s file for references to Luo Pang. There were none. So was this a new suspect? The Shan Master, perhaps? Or just another password? Or a false trail? For the moment there didn’t seem to be any way of finding out.

The inspector took a small black notebook out of his pocket, and began to write.

He had his own approach to cases, which he had worked out over the years. First, note down all actual facts about the case so far, however irrelevant they may seem. Then check they really are facts. What is actually known and what is presumed? Then consider what he called ‘pressure points’ – things that don’t add up, people whose role in the story seemed false in some way – and what action should be applied there.

‘The method’ he called it. It wasn’t infallible – nothing was, not even the Party – but it always helped.

*

Commissioner Da was seventy-five – almost old enough for the Politburo, as Bao’s colleague Zhao said when Team-leader Chen wasn’t around. Da had been on the Long March. He had fought the Japanese in Shanxi province, the Nationalists in Manchuria and the West in Korea. He had been fiercely criticized in the Cultural Revolution, then rehabilitated, rumour had it on the insistence of Premier Zhou Enlai himself. Now he sat in an office on the fifth floor where he appeared to spend all day drinking premium export-only tea and writing memoranda.

Bao Zheng, from a poor family in rural Shandong, would seem to have little connection to this darkly eminent, urbane man. But there was a link: the military. Bao had left Shandong at sixteen to join the People’s Liberation Army, and had won a Combat Hero medal during China’s invasion of Vietnam in 1979. After leaving the Army for the police, he had kept in touch with his old commanding officer on the Yunnan front. When Bao was posted to the capital, Colonel Li had told him to contact Da. Bao had done so, and the two men had taken a liking to one another.

Da respected Bao for his medal and for what he called his ‘outlook’. They shared an interest in traditional Chinese culture. And Bao was a good listener to the old man’s stories. Bao, in turn, genuinely enjoyed hearing the stories: his father had always advised him never to cultivate a relationship, however advantageous, if he did not feel genuine affection for the other person. He did not overuse the connection, either, sticking to professional, not personal favours.

‘Ren Hui is our only way forward,’ Bao explained. ‘I must have a close look at him.’

Da took the lid off his tea-cup and sniffed the steam. ‘Another minute, I think. Why don’t you just pull him in for questioning?’

‘It’s too early. I want to get to know him a bit first.’

Da nodded. ‘You know Internal Security aren’t keen on Xing Zhen Ke personnel in plain clothes. They’ll make a fuss.’ The old man paused. ‘But I’ll get everything signed off. I don’t like the way they meddle in our affairs.’ He sniffed the tea again.

They … On the floors below, people said that Commissioner Da (nobody called him the pally-sounding Lao Da, Old Da) worked for Internal Security. Da always denied it vigorously, but told Bao not to pass the denials on to anyone. ‘If they dislike me enough to say that,’ he would argue, ‘it’s best if they are also a little afraid of me.’

The old campaigner raised the mug to his lips took a sip. ‘It is ready!’

Bao Zheng removed the lid of his own cup and began to drink, too. Da was right, of course. The taste was teetering on the edge of bitterness but not falling over it. Perfect!

*

A bloodshot sun was sinking behind the gables, smokestacks, trees, power-lines, apartment blocks and TV aerials that made the skyline of Chongwen, in 1991 the poorest of the capital’s four inner districts. The air was heavy with smoke, heat and rush-hour racket – bicycle-bells, crowds jostling along the bumpy concrete pavements, and now, more and more, motor vehicles, which were demanding more and more space (if this growth went on, they’d outnumber the bicycles one day…) Somewhere, a traffic policeman blew a whistle. At whom? Nobody here knew; nobody here cared.

The taxi turned off the arterial road and was instantly back in the closed world of the hutongs. One of its passengers was Bao Zheng, now in a Western suit, patted the briefcase on his knee.

‘Remember your name,’ he told the other passenger, Lu.

‘Yes, sir. It’s Bo.’

‘Just down here, isn’t it, sir?’ said the driver.

‘That’s right.’ Bao glanced across at Lu again. Was his assistant the right companion for this mission? Lu would be good in a fight, but the best undercover operatives never got into fights in the first place. But Bao needed company. Two pairs of eyes were very much better than one. He was lucky to have an assistant at all.

The taxi pulled up by a clean, well-kept doorway and the two passengers got out. Bao watched the vehicle disappear, then walked up to the door and rang a bell.

A man soon appeared and showed the new arrivals in. They walked down a corridor, through an arch and into a well-kept yard. At the far end was a two-storey house with a facade of fresh stucco. Blinds on all its windows, except one in a kind of side annexe, kept out prying eyes. Somewhere inside it, a woman was singing a wistful folk tune.

‘How lovely,’ Bao muttered.

‘What?’ said Lu.

‘The song.’

‘Oh, yes.’

The man crossed to the stuccoed house and rapped four times on the door (Bao made a mental note of the rhythm). The door opened to reveal a stocky character in a pinstripe suit, black and white leather brogues and a bright purple shirt with matching tie. This had to be Ren Hui, importer/exporter, probably Enforcer for the local Yi Guan Dao lodge and possibly the killer of Xun Yaochang.

‘Mr Ling! Come in,’ said Ren, dismissing the gatekeeper with a flick of his hand.

The hall had thick pile carpet and what looked like silk wallpaper. Ren closed the door and bolted it, top and bottom.

‘So you knew my old friend Shi?’

‘That’s right,’ said Bao. ‘Back in Jinan days, of course. Times have changed a lot since then.’ He held out his card.

Ling Wuda. Procurement Manager, Victory Electronics Factory.

‘Shi and I went in, er, different directions,’ Bao continued. How thorough chain-smoking, Triad-obsessed Inspector Liu had been! ‘But we’ve both moved on in the world.’

Ren laughed. ‘And now you’re after air-conditioners, right?’

‘Yes. Productivity will tu

mble when summer comes. You know what it’s like.’

‘Not really.’ Ren flicked a switch and a jet of cold air swirled past Bao’s head. ‘Come through.’

A huge television dominated one corner of the next room. Xinjiang carpets overlapped one another on the floor, and the walls were hung with tapestries.

‘Drink, gentlemen?’ Ren crossed to antique lacquer cupboard and opened it. The inside had been gutted and turned into storage space for bottles of foreign spirits. Bao reined in his disgust at such vandalism and asked for a beer. American, if possible.

Ren called out: ‘Yujiao!’ The singing stopped and a young woman entered from a side door. She was tall but graceful, with long hair tumbling over her shoulders, framing a face that Bao would have found beautiful had it not been made up to look vulgar and Western.

‘These gentlemen want some American beer,’ Ren said. ‘Fetch us three, please.’

‘Yes, Father.’ She disappeared at once, then came back with three tins and glasses.

‘My daughter is the best singer in the city,’ said Ren.

Yujiao blushed but said nothing.

‘And the most beautiful,’ Ren continued.

She blushed even more.

Bao made a suitably polite comment, while an inner voice added that her beauty deserved more than this showing-off.

Having poured out the beers, the young woman headed for the door.

‘Stay and amuse us, Yujiao,’ Ren told her.

‘I’ve work to do, baba.’

‘Oh, very well.’ After she’d gone, Ren shook his head. ‘She knows her own mind, that girl. And she’s so talented. Singing, dancing, acting. She’s got a great future.’ He raised his glass. ‘Ganbei!’ Cheers!

‘Ganbei!’ the policemen replied, and drank. The singing began again, this time in a foreign language. Probably English, Bao thought, the language that everyone under thirty wanted to speak.

‘Now, this machinery you want to get hold of. It’s not easy to come by. I’ll need an advance.’

‘That won’t be a problem. Would you prefer cash?’

‘Of course.’

‘How much?’

‘Twenty per cent.’

Bao knew he had to play the part, so they haggled for a while and got the figure down to fourteen.

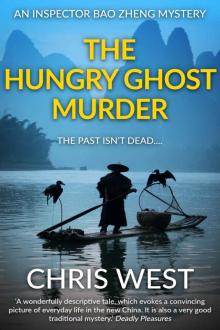

The Hungry Ghost Murder

The Hungry Ghost Murder