- Home

- Chris West

The Beijing Opera Murder Page 5

The Beijing Opera Murder Read online

Page 5

Lu was dumbstruck.

The gatekeeper began to laugh. ‘Go on. If anyone asks, you climbed over the wall, OK?’

Lu grinned and walked off as fast as dignity would allow. The man returned to his magazine – Shanghai Movie Pictorial on the outside, a Hong Kong soft-porn mag on the inside – shaking his head and muttering about the age of policemen nowadays.

*

Jasmine Ren walked out on to the stage to the usual burst of applause. From the side of the stage, Eddie Zhang grinned up at her. The young floor manager’s infatuation was as total and pathetic as ever. Who else was here? The spotlights didn’t allow the singer to see too far into the audience, but Ken and Ray were both at their usual front tables. Alone with candles, ice buckets and champagne – French, of course, not the cheap, sweet Russian stuff the hotel palmed off on tour groups or local officials. She awarded both businessmen a smile before beginning her act.

‘Welcome to the Starlight Suite,’ she said in English then Japanese. ‘I’m Jasmine, and I’m here to sing for you. Later on, it will be your turn to sing for me!’ She turned and grinned at Ken, whose karaoke version of My Way never failed to reduce the band to laughter.

‘I’d like to begin this evening with a song from America,’ (time for Ray to get a special look).

More applause. The bass began playing a C, in a slow, heartbeat pulse. Drums joined in on kick-pedal and backbeat. Jasmine felt a thrill run through her, the kind of thrill, she had decided, that only music could truly create. She was American now. She put her lips to the mike and let out a kind of moan that made even the barman stop and stare out at the stage.

After two sung verses, the guitar took a lead – another chance for her to scan the audience. Both Ken and Ray had expressed their admiration for her with compliments and presents. Both wanted to become her lover. Jasmine wasn’t interested. She didn’t have to take anything she didn’t want. She knew how baba would feel, too. He hated her having any kind of boyfriend. But she went with a foreigner, he’d go crazy. Baba in his crazy mood was not something she liked to contemplate …

At the end of the number, the two businessmen tried to outdo each other in their applause. She thanked them with more flashing smiles. No harm in flirting, of course.

Outside, Lu walked up to the doorman and tried his ID again.

‘There’s no crime going on in there,’ the doorman replied. ‘Entry for non-residents is twenty-five yuan in Foreign Exchange Certificates.’

‘Twenty-five!’

‘Or ten dollars US.’

‘Ten dollars! May I remind you that the People’s Police have a right to ‒’

‘This particular People’s Policeman is trying to get into a very popular show without paying.’

‘This is part of a criminal investigation.’

‘D’you want a word with the manager?’

‘No,’ said Lu despondently. From behind the doors, she began to sing. The young man’s inside seemed to tighten. The doorman noticed his expression and felt either pity or the opportunity for a special deal.

‘Have you got renminbi?’ he asked. People’s Money, the money that ordinary citizens use.

Lu went through his wallet and held out the contents. The doorman counted dismissively through the grubby notes.

‘Bring proper money next time. Welcome to Capitalism!’

That word was abhorrent to Lu. Capitalism meant selfishness, greed, disloyalty, immorality. But now it also meant hearing and seeing Jasmine. He slipped in through the door and joined his fellow-sinners.

*

The first set was over. Jasmine looked round at the audience again. She began to speak; Eddie Zhang tore himself away to put up the house lights.

‘We’ll be back again soon with some more music from around the world – this time, with your help.’

Ken grinned; he’d been practising. Jasmine lingered on stage to smile back at him. The lights went up. She lingered even longer. It wasn’t just Ken and Ray staring up at her but the world. A big, rich world – men in thousand-dollar suits, women in dresses that cost years’ wages for most Chinese. The one mainlander there – a young guy at the back, quite handsome, thoroughly embarrassed – stood out a mile for his feeble attempt to dress smartly.

There was something familiar about him.

‘Come on, Jasmine. Off the stage,’ the bandleader said. ‘It’s unprofessional.’

She obeyed, suddenly ill at ease. Where had she seen the young man before?

‘Who cares?’ she told herself as she retreated into her dressing room. ‘He’s just someone who’s seen me around town, and who’s found a back door into one of my shows.’

But she felt no better. The Starlight Suite was the one place where she was in charge. Who was this interloper? She would ask around.

Chapter Five

Constable Lu cycled home from the hotel in a troubled frame of mind. Ren Yujiao had looked him in the eye, he felt sure of that. But what had her reaction been?

Pleasure, at realizing that a proper Chinese citizen admired her work, not just a load of foreigners?

She hadn’t looked that way. She’d looked… unhappy in some way.

Perhaps she’d read his feelings. Women were good at that, apparently. Maybe her natural modesty had been shocked by them.

No, her show wasn’t exactly modest, but that was just a show …

Or was it? Maybe she was truly immodest. So immodest that if they were alone together, she would –

‘Watch where you’re going!’ shouted a fellow cyclist.

What worried Lu was the thought that she had been curious, and would want to find out more.

*

At work next morning, Lu felt this worry grow.

His duty that day was very dull. The boss wanted him to check more records – boring ones that revealed nothing. (The boss himself was working on that Triad file again. Lu bet that was a lot more interesting.)

All the more time for that worry to grow.

He had to find out more.

*

‘Correct ritual is always followed.’ Bao had underlined that sentence. Not assassination in an opera house. Yet the look on Ren Hui’s face when he had mentioned Xun …

He glanced up at the clock. Time to go home again. And to forget work for one evening. Forget, OK?

The inspector rode home through the diesel fumes and racket. Forget. He would cook a meal. He would do some qigong exercises. He would read. The new edition of October, the short story magazine, had just arrived. If the censors had got at it too much, he would go back to the classics. Stories to Awaken the World. The Water Margin. Or something more exotic, another one of those tales from that bizarre, far-off place called London, featuring the detection skills of Fu Er Mo Si (Sherlock Holmes).

Bao’s near neighbour Mrs Zeng was emptying a dustbin as he coasted into the compound of Tiantan Inner Eastern Building Twenty-six, the twelve-storey concrete block of flats where he lived. She smiled at him. ‘Don’t forget that dinner invitation.’ The Zengs had been very kind since the business with Mei.

Bao pushed his bike into the rack and flicked its rear wheel lock shut. ‘I won’t. Work hours are so irregular at the moment. When this case is over …’

‘You’ll be on another one.’

Bao grinned. ‘You’re right. We’ll fix a day. Next month. I won’t be so busy then.’

He took the creaking lift up to the tenth floor, and made his way along the balcony past the strange assortment of objects that even Party members end up storing outside their doors due to lack of space. Flat 1008. Home.

By most people’s standards, Bao Zheng’s apartment was enormous. Four rooms, just for one man! A sitting room at least three metres square. A bedroom almost as large, its walls lined with books. A small kitchen and a stone-floored lavatory-cum-shower (hot water twice a day, morning and evening). Flat 1008 had, of course, once housed two people.

He sat down on the one easy chair and found himself staring

at the photos on the heavy mahogany dresser. In one frame, three army sergeants shared a packet of Double Nine cigarettes and a joke, against the background of an out-of-focus Vietnamese jungle. Wan and Yi had both stopped bullets in the same action that Bao won his medal; Wan fatally, Yi to a long period in hospital, after which they had lost contact. Rumour had it that his former comrade had become moody, difficult and hard to employ. Next to it was a family group: Granny Peng, his father and mother, big brother Ming and little sister Chun, all dressed for 1 October celebrations in the late 1950s. Then a simple one of Bao in police uniform, his ex-wife Mei in a bright silvery dress from a Friendship Store.

Bao knew he should get rid of the last of these, but somehow the collection looked empty without it.

Mei had wanted more out of life than a man of Bao’s background could offer. He had thought she would make him urban and sophisticated like her. She had… Well, Bao wasn’t sure what she had seen in him. Whatever it was, it had proven an illusion.

Don’t brood. Do something.

Bao enjoyed cooking as much as eating. He set the rice up to boil then prepared some pork, cutting the salty outer skin into cubes, searing them in oil and ginger then cooking them in rice wine, soy, salt and sugar. When these were nearly ready, he took off the rice, turned the power up to full and stir-fried some beans. A feast, all done on two rings of a burn-blackened mini-hob. He poured himself a glass of beer and ate slowly, savouring the tastes he had inveigled into the apparently simple ingredients. Delicious! A bowl of stock soup followed, then a mug of tea.

Work? Divorce? Forgotten!

To round things off, a little qigong. First, stillness. Concentrate on your own breath. In, out. Then begin to move. An extraordinary sense of deep calmness began to arise in him.

Bao had only had the phone fitted recently. Its bell made him jump. He grabbed the receiver.

‘Who’s that?’

Silence. Then a feeble, frightened voice. ‘It’s me, Lu.’

‘Oh.’ Bao composed himself. ‘What’s up?’

‘I must talk to you.’

‘OK. I’m listening.’

There was a sigh. ‘Could we meet? I don’t trust the phone. People might be listening.’

Bao gave a frown of puzzlement. ‘Well, if it’s that important…’ He paused to remind himself of where Lu lived. ‘Meet me at Zhengyang Gate in half an hour.’

He glanced at Mei again, and found himself feeling sorry for her, despite everything. Who would marry a policeman?

*

Bao stood by the southern gate to the old Imperial inner city. Soft music was playing from a nearby loudspeaker. The twittering of starlings in the gate’s rafters competed with it. In front of him was Tiananmen Square, now largely dark and quiet. Dim ornamental lamps created isolated pools of half-light in its centre; around the edges, floodlights picked out the key points of the great buildings around it: the national emblem on the Great Hall of the People, the flag on the Bank of China, the portrait of Chairman Mao on Tiananmen itself, far away at the other end of the square. The grand boulevards that ran up and down the sides, that would have been thronged with traffic a couple of hours ago, were empty apart from a few bicycles and a colleague on a Japanese motorbike. A young couple walked past, hand in hand, a display of public affection that Bao still found puzzling. It seemed indecorous, somehow.

He lit a Panda and enjoyed the familiar, rich taste.

‘Inspector Bao!’

Constable Lu came into view. The young man looked terrible.

‘What’s up?’ Bao asked.

‘I – I couldn’t talk about it over the phone. Thanks for coming, sir ‒’ Lu’s voice died and his eyes fell to the ground.

‘What on earth is it?’

‘Well, sir, you know you told me to build up a dossier on Ren’s daughter. Well, I was doing that, and … She’s disappeared.’

‘Disappeared?’

‘Last night I went to that hotel where she sings. To try and find out more about her.’

‘I did say discreet, Xiao Lu. Did you find anything?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Did she notice you?’

‘I’m … not sure.’

‘That means yes.’

Lu grimaced. ‘This evening I went back there again – ’

‘You what?’

‘I went back.’

Bao took a long drag on the Panda. To get angry would be to lose face. ‘Why did you do that?’ he asked calmly.

Lu looked at the ground and mumbled some answer about wanting to be sure whether she had noticed him or not.

‘You’re infatuated with her,’ said Bao.

‘What does that word mean?’

‘You know bloody well what it means.’

‘I suppose …’

‘Anyway, what happened this time?’

‘Nothing. The performance had been cancelled. I asked why, and the doorman said Jasmine had reported sick.’

‘People get sick. Even the young and irresistibly beautiful.’

Lu blushed. ‘It – seems a coincidence.’

Bao sighed. He was always telling Lu not to believe in coincidence. ‘This doorman. Did he know you were a policeman?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And who else did you play the “Let me in, I’m Public Security” stunt on?’

Lu stared at the ground again. ‘The gatekeeper, sir.’

‘Nobody else?’

‘No.’

‘That’s something, I suppose.’

A truck backfired on Qianmen West Street, sending the starlings whirling into the night sky. Bao battled with his emotions. ‘You were a fool to go there in the first place,’ he said finally, ‘and a complete fool to go back. But you have been brave to come and tell me now. Well done for that. The operation might have been compromised. We must act fast.’

*

When Bao knocked on Meng Lipiao’s door and no one answered, he told Lu to kick it down. The constable leant back and brought his boot down just behind the lock. The door splintered and yawned open. The two officers burst into a dingy bedsit. Bao’s heart sank as he contemplated the clothes on the floor and the disarrayed bed.

‘Too late!’ Bao felt the anger at his young colleague rising again – but with it a callous professional pleasure. This surely showed they were on the right track.

A head peeped up from behind the bed.

‘Oh. It’s you,’ it said.

‘Yes. Why didn’t you answer when we knocked?’

‘I was busy,’ said Meng. He stood up, draping a sheet around his naked body. ‘You’ve damaged my door.’

‘We’ll send a man to repair it. If we’d have been the Yi Guan Dao, it would be more than your door that got broken.’

That look of instant terror again. ‘They’ve found out what I told you?’

‘No. But there’s been, well, a hitch in our surveillance operation. I’m not taking any risks. So get dressed and packed.’

‘Where are you taking me?’

‘Somewhere where you’ll be safe.’

‘Jail? Just because you dogs can’t keep a secret?’

‘Because I keep my word. It’s no problem for the Xing Zhen Ke if you get sliced up and dumped in the Tonghui River by Ren Hui and his friends. But I’ve got a conscience.’

Meng looked at Bao suspiciously. He distrusted all policemen, especially when they started talking about conscience. But he feared the Yi Guan Dao.

*

Giddy from the lift, the inspector stepped out on to the twentieth floor of the Qianlong Hotel. He padded across the thick crimson carpet to the doors of the Starlight Suite and went in. There was a bar by the door, tables and chairs in the middle, and a stage at the far end, crammed with the impedimenta of Western ‘music’: drums, electric keyboards, amplifiers and microphone stands. A middle-aged woman was polishing the bar-rail. She glanced up at the new arrival, scowled and got back to work.

Bao made his way to the stage and hopp

ed up on to it. Lu said he had been standing in the far left-hand corner. About where the cleaner was now. Ren Yujiao could have recognized him easily.

Backstage was a tatty dressing room, along whose near wall were coat racks with sequinned costumes on rusty wire hangers, and mirrors with light sockets above them, mostly empty. A door led into a smaller room that was carpeted, well-lit and sweet-smelling. Two bouquets of flowers sat in vases. Bao bent down and read the labels, one in Western writing, the other in Japanese.

He felt a tingle at the back of his neck. Policeman’s instinct: he was being watched. He turned to find a burly man with a scar on his chin standing in the outer doorway.

‘Can I help?’ said the man aggressively.

Bao smiled back. ‘I don’t know. Are you part of the band?’

‘No.’

‘Ah. I hear they put on a good show.’

‘They do. Very good. What’s it to you?’

‘I was wondering … I’ve always wanted to hear Western music. Is there any way you could get me a ticket?’

The man sneered. ‘You’d better speak to Mr Zhang.’

‘And his office is … ?’

‘Down the corridor, third right.’

‘Thanks,’ said Bao. He took one more look round the room, just to show the big man that he would leave in his own time, then left.

*

The young man with fish-bowl glasses grinned nervously as ‘Inspector Gao’ introduced himself.

‘I’m Eddie,’ he said in reply, pointing at a plastic badge on his lapel with English writing on it.

‘And your Chinese name?’

‘Kangmei. Zhang Kangmei.’

Bao smiled. He didn’t usually approve of people taking Western names, but this seemed a reasonable exception. Kangmei – Resist America! – had been fashionable in the late 1960s, when this young man would have been born. But it wasn’t ideal for someone showing the Qianlong’s guests to their 400-dollar-a-night suites.

‘How can I help you, inspector?’

‘I’ve heard good things about the show here.’

Eddie grinned nervously. ‘Yes. Jasmine is the most talented singer we’ve had in this place. Ever!’

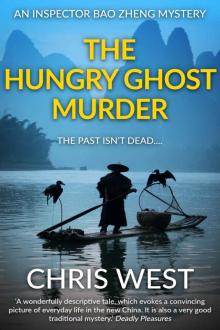

The Hungry Ghost Murder

The Hungry Ghost Murder